I think about how I should depict the built environment a lot. My idea of the built environment encompasses everything man-made, from its design to use to disposal. In design and conception, everything undertaken by manufacturers and builders is measured and orderly. In practice, everything which undermines these designs is in the details; things get put to uses they aren't intended for; circumstances unforseen happen, like natural disasters; and things are used long past the duration they were designed for. As our overheated economy demands that we make, move and retail massive amounts of stuff, at some point we will all be hip deep in malfunctioning and broken stuff.

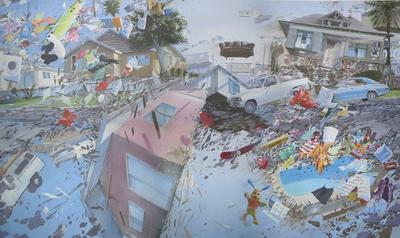

"Kipple is useless objects, like junk mail or match folders after you use the last match or gum wrappers of yesterday's homeopape. When nobody's around, kipple reproduces itself. For instance, if you go to bed leaving any kipple around your apartment, when you wake up the next morning there's twice as much of it. It always gets more and more...No one can win against kipple, except temporarily and maybe in one spot, like in my apartment I've sort of created a stasis between the pressure of kipple and nonkipple, for the time being. But eventually I'll die or go away, and then the kipple will again take over. It's a universal principle operating throughout the universe; the entire universe is moving toward a final state of total, absolute kippleization." -J.R.Isidore explaining the concept of kipple, in Phillip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?In this way, the minutia of our environment threatens its designed rationality, and when this chaos is amplified it undermines not only our operational efficiency, but our rationality of thought. Living in a contemporary American city means learning to live with the fear that suddenly the rules are going to change, by way of catastrophe; that there will be a sudden shift in the terms of our environment, which will likely seem unlikely and irrational until it happens. This kind of moment is illustrated in Adam Cvijanovic's mural, Love Poem (10 Minutes After the End of Gravity). The mural is a rendering of a worm's eye view of a mass of deterius thrown aloft. Cvijanovic is as much of a collagist as a painter. I saw a video taped lecture he gave to the Tyler grads about depicting suburbia, more than a year ago, and much of what he talked about was piecing together images from lots of different places, and making it coherent in one perspectival projection. One implicit point was that suburbs have a completely different relationship to their details and junk: They tend to hide their refuse and eccentricities more, at the expense of a suffocating sameness.

Cvijanovic's materials are worth noting as well: he works on Tyvek, which is a plastic housewrap that lets air pass but traps moisture, on the wall with house-paint mixed with Flashe paint, an acrylic(?, or vinyl) paint that is super-saturated with pigment, and dries very matte. This allows Cvijanovic to roll up any of his murals to transport them. He also collages cut-up pieces of paintings into other paintings, or will crop a painting to fit a wall.

Adam Cvijanovic, Study for 10 Minutes after Gravity Fails L.A., 2005, Flashe and house paint on Tyvek. Link to source.

Adam Cvijanovic, Study for 10 Minutes after Gravity Fails L.A., 2005, Flashe and house paint on Tyvek. Link to source.

No comments:

Post a Comment